“I proclaimed myself a Mayan prince, in the middle of Paris, not far from the Eiffel Tower. The Sun was my godfather.”

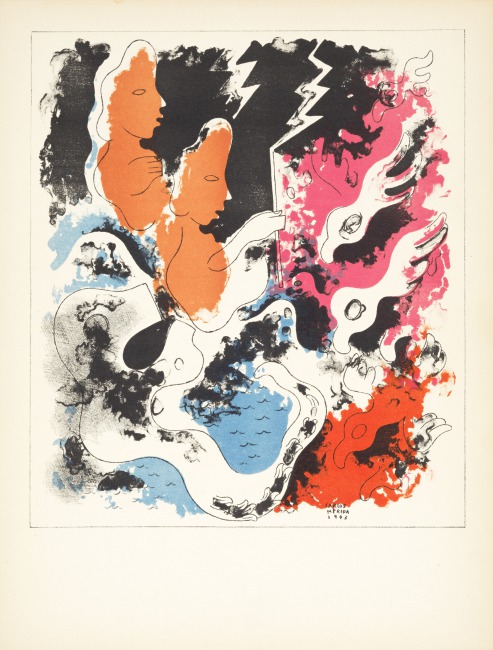

At first glance, the artist Carlos Mérida (1891-1985) appears to be a host of contradictions: a fervently anti-colonial man who embraced European artistic traditions, an indigenous artist who at times fetishized his own (and other) non-Western cultures, and a Mexican Muralist who rejected politicizing his art. These contradictions, however, imbued his works with a timeless quality. He perfected an ability to meld Western and indigenous traditions into something beautiful and new—a powerful lesson for our increasingly interconnected and polarized world.1

Since Mérida was a highly prolific artist, this exhibition represents only a fraction of his creative endeavors. The selected works, however, focus on how contemporary transnational movements influenced Mérida between 1910 and 1940. These movements would transform Mérida’s interpretation of indigenous identity and his vision for Latin American art.